Stories From World War Two - Part One.

A series of wartime adventures, or misadventures, from World War Two, involving my dad, Thomas (Tom) Barbour McNeish.

prisoner of war mcneish in white shirt

INTRODUCTION

The stories that follow are from soldiers who fought in World War Two. Those involving Thomas Barbour McNeish are as remembered by his two children and committed to this format by me, the eldest of them, encouraged by my younger brother, a Doctor of Physics, now a resident of the United States of America. The other stories are both from the written memoirs of and directly from the mouths of others. They will cover the whole of their war experiences, from the beginning until they arrive back home. I will separate their war into sections.

This is the first of them.

Part one;

From being free to becoming a prisoner.

Early Life

Tom, our dad, was born in Lesmahagow, Scotland in 1919, into a coal mining family. He had five siblings. The family moved to Denny, a small industry based town in Stirlingshire, where my Grandad sought work in the local coal mine. Tom was still a young boy. His mum, my paternal grand mum, died in 1934 aged just 45 years. His dad married again.

This brought about Tom’s first misadventure. His step mother seems to have ‘some issue’ with her step family, if not them all, certainly, based on what happened when my dad was about 14 years of age, him and his older brother Jim.

She attempted to murder both of them by putting poison in their packed lunches.

Her attempt to ‘move them on’ failed and she was incarcerated in the local Asylum, as it was called way back then, for five years.

Despite this set back, Tom went on to start an apprenticeship as a shoe maker and cobbler. A trade he stayed in for the rest of his life.

In 1939, a few months before his 20th birthday, war with Germany was looking inevitable.

Becoming a Soldier

Not long before war was declared, Tom walked a few miles from his home in Denny to a nearby recruiting centre in Stenhousemuir, where he signed on the dotted line and became a soldier in the 4th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders. One of the oldest Scottish Infantry Regiments in the British Army.

When asked years later why he chose the Army, rather than the Air Force or the Royal Navy his answer was typical of the man.

If I am a sailor and the Captain wants to win a Victoria Cross, I will have to go with him. In the Army, I can duck. Oh, and I cannot fly.

In January 1940, after a few months training at the regimental HQ, Fort George in Inverness-shire, Tom and his Seaforth colleagues, 2nd and 4th Battalions, alighted a troop train in Inverness and headed to Southampton from where they were shipped to Le Havre in France as part of the British Expeditionary Force, the BEF. If they thought being in France would take them into balmy mild weather, they were to be sadly mistaken. The winter of 1940 in France was exceptionally cold. Water froze in their vehicle radiators, drinking water froze in the bottles and armoured vehicles froze to their transporters, requiring the use of blow lamps to free them.

There they joined the other Scottish ‘line’ infantry regiments, including the Black Watch, Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, the Gordon Highlanders and the Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, supported by units of the Royal Horse Artillery (RHA), the 23rd Field Regiment, Signals, the 1st Lothian and Border Yeomanry and more, to form the 51st Highland Division, simply known as the 51st.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/51st_(Highland)_Division.

In the British Army, a Division comprises two or more Brigades and typically can have as many as forty-thousand troops. The 51st was not as big as that, but it did have more than ten thousand troops.

Many of the 51st were sent to the Metz area of northern France and positioned along France’s border with Luxenbourg and Germany to firm up the Maginot Line. That being a series of concrete fortification and other obstacles built by France in the 1930’s to hinder a German invasion of France.

In these early few months, the various units were moved about a lot, dug in, waited, re-deployed, waited, dug in, re-deployed again and on and on. A period referred to as ‘the phoney war’.

After the war my dad used to say, with a touch of cynicism;

‘we had 100 bullets and a rifle, but we were Scottish so we thought we were ready to take on the might of the ‘battle hardened’ German Army’.

Then it was real.

Towards the middle of May, the German Forces invaded France through Belgium, by passing the Maginot Line. It was sudden and fast. The 51st was outflanked and isolated from the rest of the BEF (British Expeditionary Force). They were ordered to fight on, under the direct command and orders of the French High Command, specifically, the French Third Army, led by General De Gaulle. It was hoped that would encourage the French to fight on.

Some have opined that another reason to keep the 51st fighting in France, was to keep the German Army divided and, by doing so, reduce the pressure on the main bulk of British and Allied Forces who were retreating from the battlefield to get back to Britain via the French port of Dunkirk.

By the 10th June 1940, things were looking bad for the 51st. The majority of the British Expeditionary Force, some three hundred and forty thousand strong, had already fled France through Dunkirk, between 26 May and 4 June (Operation Dynamo) and were back in Britain, leaving the ten thousand or so troops of the 51st in France. Most of these troops had no idea that Dunkirk had happened and that they were now, to quote one; ‘sacrificial lambs’.

The allied troops who missed out on Dunkirk were ordered to head for the port of Le Havre, where a flotilla of naval ships and small craft would transport them back to Britain. Ironically, the same French port many had arrived at a few, disastrous, months earlier. This withdrawal went under the codename, ‘Operation Cycle’.

The British War Cabinet was kept up to date with their progress as they moved south along the Somme corridor to Le Havre, by regular ‘classified’ communiqués from senior officers in the field.

These communiqués, now declassified have been prepared for public viewing by the Historical Section of the Cabinet in a document entitled;

‘The Fighting in the Saar and South of the Somme’.

Following is a small part from that official document, dated 10 June 1940 that covers only a day or two, a miniscual part of a war that lasted the best part of five years;

“10 June - 51 Division - Beginning of Withdrawal”

‘The movement of troops began after nightfall on 9th June and continued through the hours of darkness.

The bridges over the rivers Arques and Eaulne were blown and the 1st Lothian and Border Yeomanry moved back through Arques and St Aubin to Longeuil (M. 1366) and Flainville (M. 0965). The enemy lost no time in following up the withdrawal from the east and soon made contact on the Béthune river line.

The 4th Seaforth (152 Bde) defending the rail and river crossings of the Béthune at Arques La Bataille came under heavy mortar fire about 10.30 hrs. From this time onward the Germans tried hard to effect a crossing but the stubborn resistance of the Seaforth, combined with the accurate fire of 1 R.H.A. Regt. kept them at bay. Enemy transport was set on fire and parties of motorised infantry were shelled effectively as they left their trucks. When the enemy at last succeeded in getting close to the bridges the posts of the Seaforth were withdrawn; but the R.H.A. guns were then able to open up on parties of Germans who endeavoured to repair one bridge. These were driven off after suffering many casualties. The Seaforth continued to endure mortar fire but about 18.00 hrs enemy activity died down, not only here but on the flanks of the battalion.’

Many if not all ‘official’ documents tend to be coloured by political propaganda, theorists who were not on the battlefield and perhaps issues of national security. I therefore chose that part of the declassified document for a reason.

I am in possession of the memoirs and stories from several soldiers of the 51st Highland Division who fought and suffered in the same arena and time referred to in the official narrative. What follows therefore is a few experiences of just three of these front line soldiers, not coloured by politics or theories. In telling their stories I hope to bring a reality to that period of the war in a way the typed words of the Official Documents cannot.

The soldiers I refer to are; Thomas McNeish (Tom), 4th Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders, George Wedgbury (George), 1st Lothian and Border Yeomanry and Don Smith (Don), 2nd Battalian, Seaforth Highlanders.

First Contact:

Tom’s first introduction to real combat came on an early summer’s morning in an apple orchard close to a small stream. He and a colleague, a Bren gun team, were set up for the night in a shallow, self dug, firing pit.

In the predawn they heard some distant thumps coming from somewhere in front of their position, followed a short time later by a series of matching explosions to their rear. One of the ‘squaddies’, slang for soldiers, shouted to the sergeant, ‘that was too close for comfort, will you get in touch with ‘battalion’ and get them to ‘cease firing until they get their range sorted out’.

When the sergeant said,

‘I do not speak German’,

the cold realisation came over them; this was real, they were under enemy fire!

Bren Gun:

“Bren Machine Gun was a British adaptation of a Czech light machine gun. The name, Bren was an acronym from Brno, the town where the Czech gun was made and Enfield where the British version was manufactured.”

A later incident involving Tom, somewhere in the Abbeville area, showed how rules dreamt up in peacetime did not pass the ‘smell’ test of actual warfare. A few Bren guns were positioned in front of and protecting a Royal Horse Artillery (R.H.A.) battery. They were spread out along a long ridge looking down over sloping ground to a forested area, where it was suspected German troops were secreted. On command, the battery of British Bren guns along the ridge began firing into the forest. In keeping with the rules laid out in the field manual, every fifth bullet had to be a tracer round. The effect of a stream of brightly lit tracer rounds, while visually pleasing, was strategically disastrous, as the position of every Bren gun was revealed to the enemy. The response was obvious. Shortly after the Bren guns opened fire, a return cluster of heavy mortar rounds bracketed the machine gun positions. The Bren guns fell silent. After repositioning the guns, Tom and his colleagues spent the rest of the day removing all the tracer rounds from their ammunition belts.

Said field manual also contained rules for the use of mortars. It insisted that for every five mortar rounds fired, three had to be harmless smoke rounds, one had to be phosphorous and one could be high explosive. Smoke and phosphor rounds hardly intimidated the enemy. It seems the German rules of engagement came from a different field manual. They dispensed with the niceties and like serious professionals pounded dad’s section with explosive rounds only.

George Wedgbury of the 1st Lothian and Border Yeomanry, historically a cavalry regiment, but in WW2, a mechanised regiment. George drove a Bren Gun Carrier, a light armoured tracked vehicle. Also known as a Universal Carrier. Much of his war at this time was in support of the Seaforth battalions.

I will now relate, using his actual words from small section of his typed, but unpublished memoirs, The Real Fighting Begins, about one of his encounters with the enemy, near Abbeville, as they attempted to get south to Le Havre;

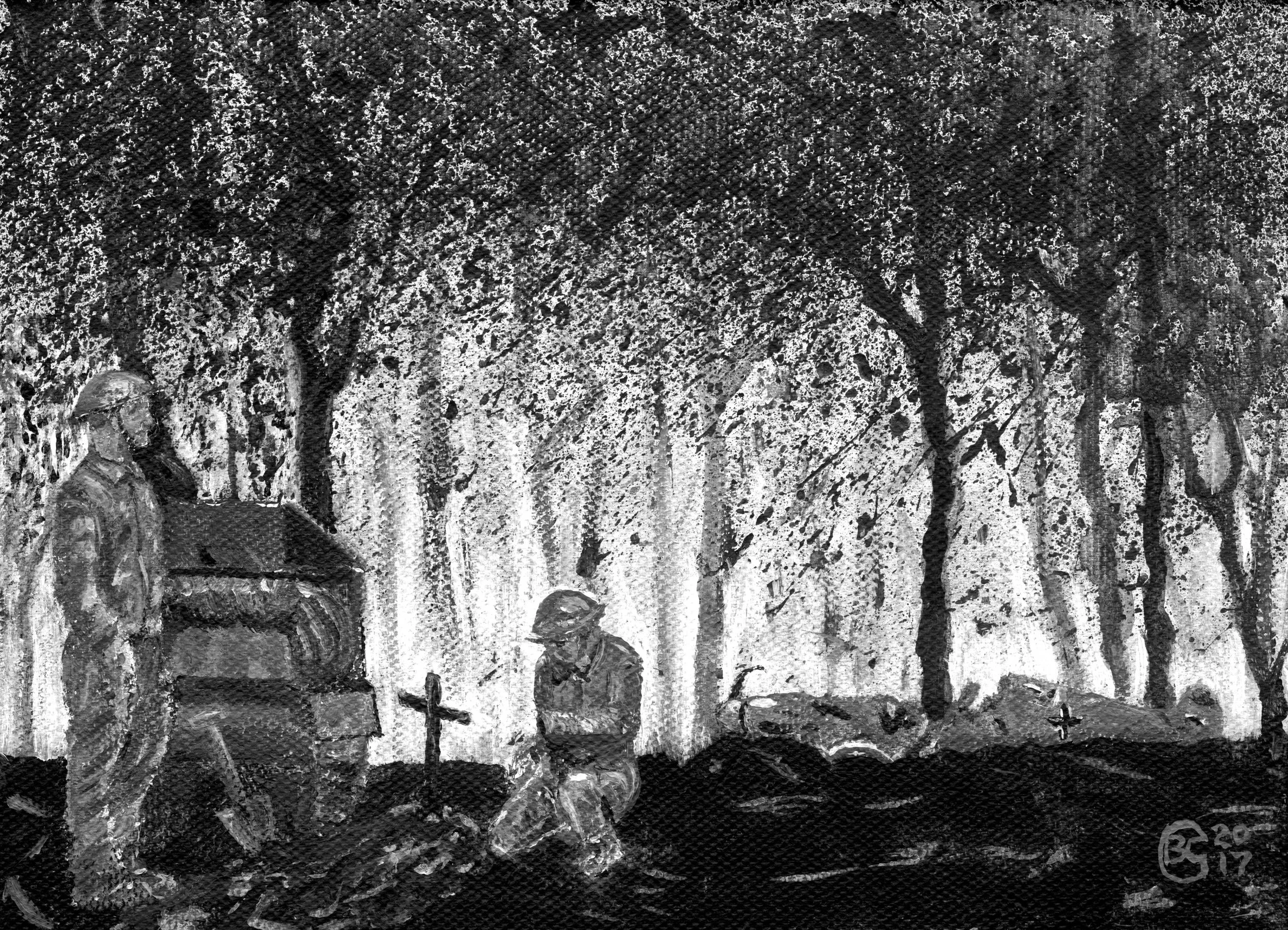

‘Under cover of darkness, our troop, number 4, with three carriers (Bren Gun) and nine men, moved into a small wood between the two squadrons,(A and C). Regimental Headquarters was a few miles behind us in a dense wood. We did guard duty and all night we could smell something terrible. In the morning we found a crashed German aircraft, burnt out some fifty yards from us. It must have crashed a few days before because the pilot, who had apparently been alive for a while, as he had crawled some distance away, was a mass of maggots, hence the smell; we buried him and put a small wooden crass at the site.

Burying a fallen enemy. Drawing by George Wedgbury of the 1st Lothian and Border Yeomanry

Just as dawn was breaking on the third morning, the silence was shattered by the sound of machine gun fire from the direction of the village where C Squadron was. (Bray les Mareuill) I remember thinking, ‘that’s not a Bren Gun, sounds like a Tommy Gun’; the Germans were equipped with these.

The Tommy Gun was properly titled the, ‘Thomson Submachine Gun’. It was patented in 1920 by an American, John T. Thompson. It weighed almost 10 pounds (4.5 kg) empty and fired .45-calibre ammunition. The magazine was either a circular drum that held 50 or 100 rounds or a box that held 20 or 30 rounds.

After a few minutes of machine gun fire, the big guns started and we could see that C Squadron was being attacked.

It was a beautiful morning, not a day one should have to die, but as it turned out, quite a few did just that.

The Lieutenant ordered Sergeant Brown, gunner Sam Jones and I to take him in a carrier and find out what was happening at C Squadron. We got to the village to find them under heavy attack. The Lieutenant said he would stay with them and ordered us to go back to the wood and join our colleagues. When we got there we found that the Germans had moved in and our troops had retreated back to the village to rejoin A Squadron.

Sergeant Brown, Sam and I, had hidden our kit in the wood when we left there earlier. Now there were Germans all over the place. Sergeant Brown, who had got married when on leave, before the move to France, had only a week with his bride before we sailed. Since we got to France, he received letters, almost weekly, from his wife. He decided to go and get them before we joined C Squadron. As he crossed open ground and got close to the wood, a Tommy Gun opened fire and he was gunned down. He had not reached the letters he died for.

Seeing there was nothing we could do for him and seeing our route to A Squadron was blocked, we decided to return to C Squadron. We were fired on as we came into the village but escaped without being hit. We found Lieutenant Dundas and explained what had happened. Our situation was perilous, so the order was given for us to evacuate our position and head back to join A Squadron. As we again passed the wood where Sergeant Brown had been shot, we were fired on again, but managed to get through unscathed and join A Squadron’.

Risking all for love. Drawing by George Wedgbury of the 1st Lothian and Border Yeomanry

The German onslaught continued over the next few hours and by the time it eased off, I was the only surviver from the four who had set out together on that lovely summer day in the Bren Gun carrier. Sergeant Brown, Sam and Lieutenant Dundas were all dead.

Don Smith of the 2nd Battalion, Seaforth Highlanders was also in the vicinity of Abbeville, part of a Bren gun detachment situated to the south of a densely forested area. Their role was to guard a crossroads and support troop carrying lorries making their way south to Le Havre, ahead of Rommel’s Panzer divisions, who were hell bent on cutting them off.

Don and his team had been holding that position for a few hours with little to report; What follows his words;

“Suddenly, out of the forest came the enemy. Both on foot and in armoured vehicles, including tanks. I remember thinking, ‘The Bren gun is an accurate weapon. But it has no spread, just direct fire. It will be useless if they start firing shells at us.’ Then the tanks opened fire. We had no chance. We were completely outgunned. My friend George (not George Wedgbury) was hit and killed. We had been friends since our schooldays and joined up together. I could do nothing for my friend and with our gun destroyed and under heavy fire from the approaching Germans we did the only thing we could, get away from there. After a few hours I caught up with my battalion. I had been wounded, not too bad, so I was still mobile. I was taken to the field first aid station where my injuries were treated. Soon afterward I was transferred to a field ambulance and joined a group heading south.”

Returning to Tom and his first face to face encounter with the enemy, a few miles south of Abbeville, near Arques La Bataille, on the banks of the Béthune river, a few miles inland from Dieppe. His group was holding a farm building when enemy troops attacked them. As they fired their rifles and Bren guns at the on-coming German troops, the returning machine gun fire, was more intense than their’s, making the tiles on the farmhouse’s roof dance and shatter with the impacts. Dad’s unit stayed firm and after a brief and intense fire fight, the Germans pulled back and dad’s platoon moved on.

Target Practice:

A short time later Tom again saw the enemy, this time seriously ‘close up’ and personal.

They were in lorries being moved to a position up river from Arques La Bataille when their convoy was ambushed and hit with mortar fire. The first they knew of the ambush was when the leading truck was blown up and landed on its side on the road, blocking the convoy’s progress. To use dad’s on words, they were like ducks in a shooting gallery as mortar and rifle fire rained down on them. He was in the second truck. It was being strafed by heavy gunfire and a lot of his colleagues were being hit. He was powerless and had lost his rifle in the confusion. He took the only course open to him and dived out into a ditch on the opposite side from the source of the gunfire. He took cover in the ditch for a short while as he worked out what to do. Then he saw German soldiers advancing out of the trees on the opposite of the road and moving in on the trucks, shooting soldiers as they closed in. Dad was convinced he was going to be shot. He did not have a weapon. He scrambled out of the ditch into a wheat field that rose away from the road and over a small hill.

As he ran and crawled up the hill he could hear bullets zing past his head and hit the ground near him. He looked around to see four or five German troops lined up in the road taking pot shots at him and laughing. It looked like they were having a bet as to which of them was the best shot as each in turn fired at him. Bullets continued to hit the ground around him and zip past him. He made it over the hill and into cover, eventually getting back to the British lines.

He told us that the sound of gunfire sounded different, depending on where you were as the shot was fired. The heavy thud was heard when at the safe end of the gun. However, when at the target end, it was more of a crack and if the projectile passed close. it sounded like a cross between a noisy bee and ripping cloth.

He had no idea how he survived that day and put it down to Devine intervention.

(Author’s note: I was once at the target end of the shot from a heavy calibre rifle. Dad’s description was accurate.)

Back to Don, this time on the outskirts of St Valery en Caux. They were sort of knocked off in various places, but strangely enough, (1:01) we were at St Valery, just outside a place called Golden of the Roses, (1:06) and this is where a big, well what we call a, a big attack came, (1:16) and there was no chance that they gave anything.

(1:19) There were tanks and everything coming across, infantry of the lot. (1:25) All we could do was just follow the ground, put backs on to us, (1:29) get ready just to keep it. (1:34) Well, as I say, shells started coming over like, you know, (1:38) like one of these high explosives blew up over the top of us.

(1:44) That's when I got that piece in the head and the piece in the back. (1:47) That's how I finished it off. (1:49) But I did notice later, I was talking to Sergeant Mitchell, (1:55) Tony Mitchell, he was out of the 4th Battalion, A Company, (1:59) and he was, it was him, it was him that told me what had happened to them.

(2:10) They got killed outright at that point, as I say. (2:15) I mean some of them, my dad was lucky as well. (2:21) You know, he was lucky he got to be a prisoner.

(2:24) Some didn't get to be prisoners. (2:27) That's why, Ian, I can't give you anything up till, (2:36) I think the middle of January, just after Christmas, (2:43) that was 1940. (2:54) They moved me up to this transit camp.

With Dunkirk now history the German Forces, led by Field Marshal Rommel, were soon back up to full strength and they harried and fought the beleaguered and vastly outnumbered, 51st and their French colleagues, as they tried to reach the French port of Le Havre, where they hoped there would be ships to get them back to Britain.

Cut off from any support, and running out of ammunition and food, reaching Le Harve was a forlorn hope.

At Abbeville they dug in to resist and throw what they had at the enclosing enemy.

The rifles and ‘bren’ guns of the 51st, were no match for the German tanks and artillery.

They were outnumbered and lost a lot of men before finally being forced back to the French coastal port of St-Valery-en-Caux, where, on the 12th June, 1940, they surrendered and were taken into captivity.

And so began nearly five years of hell for my dad, not just him. It started by being marched, then crammed into barges and railway cattle wagons as they were moved east for about one thousand miles across Europe. Those who survived, because many didn’t, were deposited in prison camps across the width of Germany and Poland.

Dad found himself the guest of the German authorities at Stammlager XXA, Torún, east Poland.

(Stalag is a contraction of Stammlager which in turn is the short version of Kriegsgefangenen-Mannschaftsstammlager, which means ‘war prisoner’ ‘enlisted’ ‘main camp’. Stalag therefore meaning, ‘main camp’.)

Six times he tried to escape, but lacking the language and failing to link up with the Polish resistance to aid him, each attempt ended in failure, leading to beatings and solitary confinement. When not in solitary or on the run, he spent much of his time working on farms or in forests.

Many prisoners, my dad included, resented being made to work in this way, not because of the work, which was better than rotting in camp. What they resented was helping the German war effort. So, if given half a chance they would sabotage the task they were given.

What follows is one of several Second World War, ‘misadventures’.

He experienced many ‘misadventures’ some before capture and some whilst in captivity.

According to my dad, the biggest misadventure, was getting captured in the first place.

I start with However the few I will highlight are situations that took place whilst a prisoner. aused by his belligerence and his attempts to ’thwart’, if even in a small way, the German War effort. While I attempt to inject a smidgeon of humour, based on the way dad related the tales, remember, the risk of a beating, solitary confinement or even a firing squad was always a possible outcome.

Target Practice: On one occasion dad was in a small convoy of trucks driving along a road lined with trees on one side with a field of grain on the other side that formed a gentle slope to a ridge line in the distance. The convoy was suddenly ambushed from the trees, the trucks stopped and everybody bailed out and dived into the ditch on the far side of the road. It soon became apparent that they were losing this fight so dad and a bunch of others made headed through the corn and up the slope to make good their escape. As he was crawling and crouching while attempting to get to the top he kept hearing bullets zing past his head. When he sat down to look back through the corn back to the road he saw a group of a few German infantrymen taking turns to take pot shots at him and the other escaping Brits. Dad didn’t think this was funny but the Germans were having a hilarious time egging each other on and obviously criticizing each other’s marksmanship. Fortunately the soon got bored with their game and our dad made his escape by crawling through the corn up and over the ridge.

Trade Goods: After being locked up in POW camp they eventually received Red Cross prisoner parcels. Each prisoner was supposed to get one of these every month but the supply was intermittent. The parcels contained goods that were both scarce and desirable in wartime. American parcels often contained a tin of coffee, a tin of butter, a tin of American cigarettes, chocolate, hard candies and other items that were otherwise totally unavailable to the POWs, guards and local civilians. While these items were of use by the POWs, they were much better used as trade goods with the guards or local civilians. Most of the items in the parcels could be traded through the wire of on working parties for eggs, potatoes and other vegetables that were used to bolster their otherwise meager rations of fifth of a loaf of rye bread and a bowl of ‘soup’ per day. Our dad became quite the egg baron in his camp, trading for eggs and supplying them to his fellow POWs in trade.

The Great Escape: Since our dad was an ordinary soldier by the Geneva Convention he was obliged to work for the Germans so long as that work was not in direct support of the German war effort whereas officer POWs were not so required. For our dad this requirement meant being detailed to various work parties, mostly on farms and other agricultural activities. He was often billeted on these farms for extended periods of time. Walking away (escaping) was pretty easy to accomplish although they were usually caught quickly, returned to camp, and sentenced to 21 days of solitary confinement. The motivation to ‘escape’ was often because the guards were a pain or their socialisation with the residents of the farm had become problematic.

On one occasion he and his buddy ‘escaped’ from a farm for the usual reasons but were not quickly recaptured. After a few days they decided to take their good fortune more seriously and head for the port of Danzig, today’s Gdansk, where they might be able to stowaway on a neutral ship and make good their escape from captivity. They travelled carefully from Torun where they were interred and indeed eventually arrived in Danzig. At the port they could see a Swedish ship tied up to a jetty and separated from them by a high wire mesh fence with barbed wire on top. After waiting patiently for the middle of the night and for the coast to be clear they started climbing the fence only to be immediately challenged by armed guards. They surrendered rather than be shot, were roughly interrogated and arrived back in camp after a few scary days to another 21 days in the cooler. That’s as close as dad ever came to making good on an escape attempt.

Bren Gun:

A later incident showed the total stupidity of ‘rules’ developed in peacetime. A few Bren guns were positioned in front of and protecting an artillery battery. They were spread out along a long ridge looking down over sloping ground to a forested area, where it was suspected a number of German troops were secreted. On command, the battery of British Bren guns along the ridge began firing into the forest. In keeping with the rules laid out in the field manual, every fifth bullet had to be a tracer round. The effect of a stream of brightly lit tracer rounds, while visually pleasing, was strategically disastrous, as the position of every Bren gun was revealed to the enemy. The response was obvious. Shortly after the Bren guns opened fire, a return cluster of heavy mortar rounds bracketed the machine gun positions. The Bren guns fell silent. After repositioning the guns, Tam and his colleagues spent the rest of the day removing all the tracer rounds from their ammunition belts.

Said field manual also contained rules for the use of mortars. It insisted that for every five mortar rounds fired, three had to be harmless smoke rounds, one had to be phosphorous and one could be high explosive. Naturally the ammunition supply reflected this rule. Smoke and phosphor rounds hardly intimidated the enemy and they paid scant attention to the flimsy high explosive rounds.

The Germans, seemed not to have read the same field manual. They just came on like professionals; my dad’s unit left the area.

Some time later he finally saw his first Germans as they attacked his position in front of a small farmhouse. As he fired his rifle at the on-coming troops, their machine gun rounds made the tiles on the farmhouse’s roof dance with the impacts. The Germans eventually pulled back and dad’s platoon moved on.

A short time later he again saw them, this time seriously ‘close up’ and personal.

trucks they were travelling in were ambushed along the road. He dived out and into a wheat field leading up over a small hill. As he ran and crawled up the hill, he looked around to see German troops lined up in the road taking pot shots at him and laughing. It looked like they were having a bet on who was the best shot as each in turn fired at him. He made it into cover and back to British lines eventually.

Another reason to keep the 51st fighting in France, was to keep the German Army divided and, by doing so, reduce the pressure on the main bulk of British and Allied Forces who were retreating from the battlefield to get back to Britain via the French port of Dunkirk.

My heroes are all those young men who volunteered to stop a virus that was sweeping across Europe some eighty years or so ago. Each and every one of them knew the risk and that their chances of not surviving were considerable. Men like Don Smith, George Wedgbury, my dad and thousands more. So, while I chose my dad as my hero, I do not chose him to memorialise him, but through his story, remind people of what he, George, Don and so many others did to rescue our freedom, and in particular to pay tribute to the thousands who paid the ultimate sacrifice in that endeavour.

It started for these brave men, boys mostly, when they volunteered for the army at the outset of World War Two in 1939. My dad, Thomas Barbour McNeish was nineteen years of age, a cobbler to trade, when, in the September of that year, he walked from Denny to a recruitment centre in Stenhousemuir, and signed up to join the Seaforth Highlanders. He soon found himself immersed in training at Fort George, near Inverness and after three months, January 1940, he was issued with a Lee Enfield bolt action rifle and 100 rounds of ammunition and shipped out to France as part of the 51st Highland Division, finding himself stationed at the northern end of the Maginot Line near Metz They were quite separate from the rest of the British Army.

A few weeks into the hostilities, the Highland Division were fighting alongside the French Army, some way inland from the English Channel coast line. Meanwhile, the main bulk of the British Army, now facing an inglorious defeat, had retreated to Dunkirk, where between 27 May and 4 June, they escaped from the fighting in France, leaving dad and his colleagues of the Highland Division to battle on.

Hopelessly outnumbered and outgunned they fell back along the line of the River Somme arriving near St Valery sur Somme in late May. They were completely outflanked by strong mechanised and infantry forces and as a result cut off from their supply bases at Le-Havre and Rouen.

Cut off from their bases, they fell back to St Valery-en-Caux on the channel coast where they attempted to hold a perimeter while awaiting rescue from the sea. However, on the 12th of June 1940, having virtually run out of ammunition and food, they surrendered to general Erwin Rommel. More than ten thousand troops of the 51st Highland Division, mostly Scots, became prisoners of war. There might have been a different outcome if earlier action had been taken, but Churchill, as a political bargaining tool to the keep the French from capitulating had delayed efforts to rescue the 51st; now it was too late.

During the pre capture days, when fighting down the Somme, many men died, including all five of Don’s close friends who he trained with. Don himself was struck by a shell and lost part of his right hand. George also lost friends, most tragically, his Sergeant who, under heavy fire returned to the building they had just retreated from to retrieve his pack that contained letters from his new bride, their wedding just a few weeks before he embarked to France. He did not make it and George looked on helplessly as he was killed. My dad’s convoy came under heavy shelling, resulting in several of his colleagues being wounded, some fatally. Dad received a minor head wound and was thrown from his demolished truck into a ditch. When he gathered his wits about him, German foot soldiers had emerged from the adjacent forest and were calmly walking amongst the wrecked trucks, shooting soldiers. Dad got out of the ditch and ran up rising ground away from the carnage. As he ran he heard German voices and laughter as some fired at him, bullets hitting the ground around him. He did reach the top of the rise and reunited with others of his regiment. Till the day he died, he could not explain how he was not shot that day.

Captivity began on foot as they were marched for days across France. Sleeping was a simple process. Lie down under the stars. No huts, no tents. If they stopped for the night near a farm with a barn, that was luxury.

Then it was trucks, barges and trains. When the latter, they were packed into cattle wagons. With up to seventy prisoners in one wagon, standing room only was the only option. Ventilation in such wagons was a single one foot square opening at one end, with barbed wire nailed across the opening. The prisoner often spent as much as three days in these wagons, without a break as the trains kept moving east. When they eventually stopped and the doors were open, most of the standing prisoner had dysentery and those that had managed to lie down were dead.

After some weeks dad was imprisoned in Prison Camp XXA, Torún, east Poland, not far south of Gdansk, or Danzig as it was called in those days. Rations consisted, a fifth of a loaf of black bread and a bowl of soup a day. At the beginning the bread was okay and the soup had recognisable with vegetables and some protein in it. As time passed the ‘bread’ became sweepings and the soup became warm water.

Private soldier were obliged to work. He volunteered to be a farm worker because it allowed him access to foodstuffs not available in camp that he could barter his Red Cross rations for. The POWs were sustained by Red Cross parcels. They were supposed to receive one parcel each week but got far fewer, and sometimes none for months. The parcels contained tins of coffee, American cigarettes, butter, chocolate, sweets and other highly desirable products. Many used to trade in the camp , but most used to barter for potatoes, carrots, eggs and other staples from local farmers. It was these staples that kept them alive through the next five years.

Dad escaped a few times; well he walked away from the farm he was working on, but with little success. When recaptured, prisoners were roughed up and subjected to 21 days solitary confinement. He was also subjected to the cruel, Long March toward the end of the war, when the Germans emptied the camps and march thousands of undernourished, poorly clad prisoners, in late winter conditions, back to Germany. Where, near Hamburg, the Germans melted away, leaving Allies to set Dad free.

Dad died in 1974, aged 54 years. His experience scarred him but did not bow him. He was a principled, non judgemental, decent human. When he died, one year after my mum, he had no savings, and was, in terms of todays definition, in poverty, living in a council house in one of the poorest estates in Glenrothes. But he was not in poverty, he and mum had a loving relationship, he had five years experience of how to survive and understand the value of things and the value of life. He was the bravest person I ever knew. His legacy to his two sons was simple, be ethical, be fair, work hard, do not judge others, be honest and if you cannot afford it, learn to live without it.

Statement of V. HÖVEL, COMMANDANT Stalg XX A. THORN Poland

The March of Stalag XXA from Thorn to Zarrentin ( 20 Jan to end of Feb 1945 )

“During the night of 19th / 20th January, I received an order to leave THORN on the morning of 20th January with the inmates of the Stalag and to proceed in the direction of BROMBERG.

Months before, an operational order had been prepared for this eventuality and everything had to conform to this order. The detailed orders for the preparation of this order had come from the Commandant of Prisoners of War, Generalmajor IHSSEN, in conjunction with the Commandant of the training camp at THORN. Oberstleutnant von TIEDEMANN had been nominated as the officer responsible for the preparation of this order at the Stalag.

In view of the rush of work which a new Commondant has to go through, I did not find time to study the operation order, but got Oberstleutnant von TIEDEMANN to give me a gist of it. Later on, I studied the operation order in detail. But at the time of the departure I was not completely conversant with its details and, therefore, Oberstleutnant von TIEDEMANN remained responsible for the departure in accordance with the operation order. This actually happened.

This operation order provided for the departure to take place in accordance with the various possible directions of the enemy’s advance.

The actual situation required the Stalag to march on the 1st day, i.e. the 20th January, in a westerly direction to BROMBERG and then further on to NACKEL, where we were supposed to occupy the alternative quarters. Any further orders for the continuation of the march would come from the Commandant of Prisoners of War, Generalmajor IHSSEN. As, however, NACKEL, which is 15 km West of BROMBERG, was already occupied by the Russians on the 20th January, the part of the operation order referring to the continuation of the march was already out of date on the first day, and thus confusion ensued. During the night of 21st / 22nd January an order was received from the Commandant of Prisoners of War to march from BROMBERG in a northerly direction to FLATOW and not to NACKEL. That was the last order from the Commandant of Prisoners of War XX A.K. As from the 22nd January, Stalag had to rely on its own resources, but under great difficulties continued its route still further North and then West - partly by marches rendered extremely difficult through snow and ice - and could then make contact with the Commandant of Prisoners of War at XVII A.K. and later. As the enemy was following close behind - about one day’s march behind us - those first days, that is the time up to the end of January, were very strenuous for the prisoners and the German staff.

With greatest of difficulty provisions were provided, (very often they were in short supply) and accommodation was obtained. The prisoners were accommodated mainly in large barns on farms. As field kitchens were not taken along, kettles etc. had to be taken from the farms to help out. Nor did we have the necessary transport facilities. Many lorries broke down, a great deal of luggage had to be abandoned in order to get on and to avoid falling into Russian captivity. We lost many prisoners flight, illness and hundreds of prisoners lagged behind and were picked up further back by other units or by police patrols. Taking rest into consideration, on an average, 25 to 30 km were covered daily.

As I have no maps at my disposal, I can quote the route only by memory, and, naturally, small errors will occur.

The march began on the 20th January, with BROMBERG as goal. The 21st January was a rest day. We left on the 22nd in a northerly direction towards FLATOW. About 20km North-East of NACKEL, a home guard company with about 1000 prisoners of war moved into billets on 22nd January - I cannot remember the location without a map. During the night of 22nd / 23rd January, this place was encircled by Russian tanks and nearly all prisoners, including several Englishmen, fell into Russian captivity.

The march was continued via VANSBURG, USEDOM, WOLLIN, SWINEMÜNDE, Training Camp at GROSS BORN, BÄRWALDE, BAD POLZIN, DEMMIN in POMERANIA, SCHWERIN, HAGENOW, ZARRENTIN in MEKLENBURG. Arrived there towards the end of February 1945. Here contact was resumed with the Commandant of Prisoners of War at XX A.K., Generalmajor IHSSEN, who had arrived at HAGENOW. ZARRENTIN had been decided upon as the final destination where the Stalag was to wind up its affairs. This meant the handing over of all prisoners of war. These were grouped together into columns and after three weeks were taken to the workshops of the State Railways in MADGEBURG, HANOVER, BRUNSWICK, LEHRTER, STENDAL, HAMELIN and elsewhere and were thus taken off the strength of the Stalag. The Stalag only kept its own soldiers. The reason for the employment at the railway workshops was to place sufficient prisoners of war at the disposal of the railway administration in order to repair the considerable damage wrought on the railway network.

The Stalag received the orders to march via DÖMITZ on the ODER, SALZWEDEL, GIFHORN to the training camp at FALLINGBOSTEL, in order to be finally broken up there. As the Americans were very near us , the Stalag had to depart again via LÜNEBURG to DÖMITZ, where troops had to be handed over for frontline service on the LOWER ELBE sector. The march continued back to ZARRENTIN and then to HAMBURG, where the Stalag was placed under the command of the Commandant of Prisoners of War at X A.K., who ordered the final dispersal of the staff of Stalag XX A. Then a short march to the North of HAMBURG, and, at the beginning of May (1945), I fell into English captivity in the neighbourhood of KENSBURG.

To conclude, I should like to add the following on the subject of the above-mentioned march;

The departure was extremely hurried. Had it been ordered to commence a few days earlier, that is on the 17th or 18th January - and that would have been possible - everything could have been arranged more quietly which would have been to the advantage of the troops and the prisoners of war.

It was a great disadvantage not to have field kitchens or make-do equipment such as kettles for the troops and the prisoners of war.

Ration supply should have been more certain.

Insufficient transport facilities for such long marches with prisoners of war, who were not used to them anymore.

I have made the above statement of my own free will and without compulsion.”

(Sgd) V. HÖVEL

Signed in my presence (Sgd) G. HAY, Capt. L.D.C. 8th February 1946

Dad died in 1974. He was 54 years of age, so young. He never really recovered from his years in captivity, nearly a tenth of his life, and never forgave the powers that be, or the media, for ignoring and staying silent about the bravery and the sacrifice of the men of the 51st Highland Division and their capture at St-Valery-en-Caux.