The Inspection

A true, if a bit tongue-in-cheek, look at police management in action, involving responsibility cravenly dodged and power needlessly exerted

I was in my ninth year of police service and in my second week in the rank of Sergeant.

a newly promoted sergeant

I had never, in all my nine years of service, worked in a station that had a sergeant and, until being promoted the previous week, had never attended a shift briefing. Now I was responsible for delivering them. I remember looking around at the assortment of officers arrayed around the briefing room on my first day and thinking, ‘most have as much, if not more service than I have; why am I briefing them? Do they not know what to do?’

Other factors that contributed to an interesting few early days for me:

I had never worked in this Police Division nor had I ever set foot in this station. I did not know the area, the staff, nor was I familiar with the ‘quaint’ customs and foibles of the division, or more importantly, its senior officers. I was on a steep learning curve.

The Inspector in charge of the station told me on the Tuesday, whilst locking his office door and departing for the day, that he would not be about for a few days. It became crystal clear why in his next statement,

“The Superintendent will be here to carry out the annual station inspection over the next two days, starting tomorrow morning. Don’t worry,” he added, “he knows where to find the books. Don’t say much and do not, under any circumstances, contradict him; just make him tea and keep him sweet.”

Then he was gone.

What I now relate involves a smidgeon of mockery and perhaps a tad of intended humiliation by a senior officer to a minor rank. Behaviour that in today’s world may be regarded as workplace bullying, but some forty years ago would be regarded as nothing more than good management designed to toughen up a new sergeant.

The reader is free to decide. Me, I thought it was amusing and a tad unnecessary.

So, ‘D Day’ dawned, and I innocently, if somewhat naïvely, greeted the Superintendent with a smile and the offer of tea. He did not take long to put me in my place.

He started by giving me a superior stare, then he asked me who I was, and then, after a pregnant pause, he told me he had no time for tea and if he did find time, he would tell me, adding that he suspected I spent too much time drinking tea.

He then instructed me to remain in the room while he inspected the various books and other systems.

“Oh, and keep quiet. I will expect you to contribute when spoken to and answer any queries I have when I ask, not before. Is that clear?” I said it was, adding, “SIR!”

Perhaps a bit too forcefully, as he stared at me for a bit longer than I thought necessary.

And boy, did he inspect the books. He studied each page and each entry as though he were searching for hidden clues in a John le Carré spy thriller. I sat expectantly on the other side of the desk, hardly breathing.

To my shame, I was secretly wishing for something serious to happen in the town so I could make my excuses and leave. No luck on that front; the good citizens were on their best behaviour. Peace and tranquility reigned.

Every now and then he would, almost with a smirk, probe some entry in a log and ask if I could account for some item or other. Bearing in mind this was only my second week in the rank and also my second week in this particular station, I had no clever answers to any of his questions. In fact, I had no answers, clever or otherwise. I certainly was not impressing him.

I am convinced my uncertain responses filled him with glee. Maybe it was rage. I was struggling to pick up the signs through my discomfort. The inquisition continued unabated.

It was then that he hit me for his first six of the inspection. (Hit for Six is a cricketing and peculiarly English term. Perhaps ‘threw me a curve ball’ would be an American equivalent). You get my drift.

Anyway, what he actually said was, “Will you bring me the fire alarm test book?”

The what?

My brain screamed. In all my nine years’ service to date, I had never encountered a dreaded fire alarm test book, in fact, I had never worked in a police station that had a fire alarm. Since arriving at this station, no mention had ever been made of such an important and strategic piece of police documentation. How important I was just about to find out.

“Well? Where is it?” he snapped as I looked around.

I use that word advisedly because, while he did not shout, nor scream for that matter, although he might have considered it, his voice was demanding, as if barking an order.

He obviously saw this fire alarm test book as important. No, CRUCIAL, in fact, perhaps the most important document ever to grace the building we occupied at that time.

I scurried off and found the office typist, come receptionist. If she did not know where it was, it would be back to plodding the nightshift before the cock crowed.

Calmly, with a knowing smile playing on her lips, she led me to the fire escape door—yes, the fire escape door—a door I, up until that precise moment, had no idea existed. Next to the door was the ‘fire alarm’ with clear instructions, ‘in the case of fire, break the glass’.

It was then I spotted the holy grail of books.

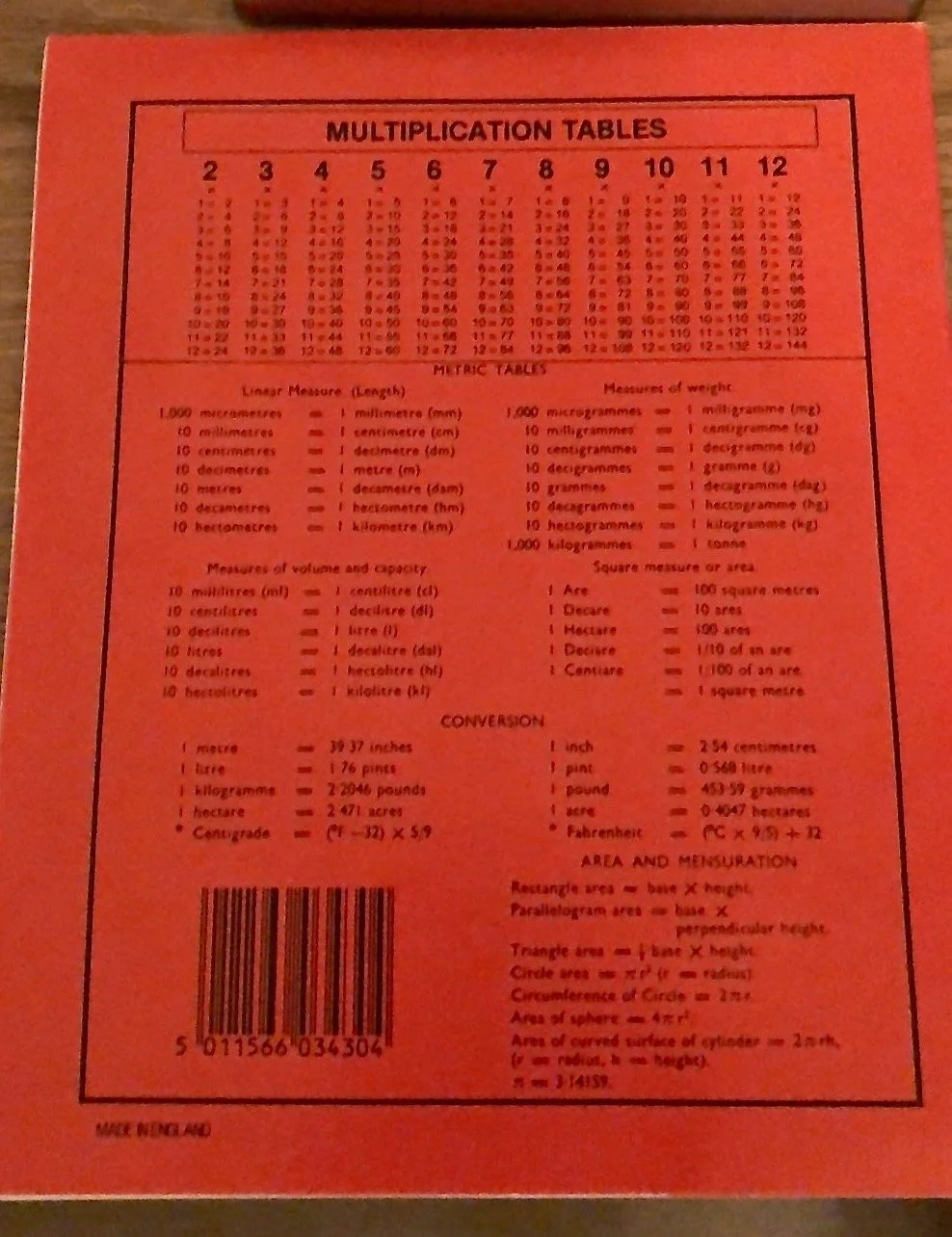

It was a red, soft-covered primary school exercise book, complete with multiplication tables on the outer back cover. It had a ragged hole punched at the top edge, through which a length of string had been inserted and formed into a loop, thus allowing said ‘exercise book’, to hang from a cleverly situated nail adjacent to said fire escape door, thus transforming an innocent children’s exercise jotter into a strategically important ‘fire test recording’ document.

primary school exercise jotter, now masquerading as the fire test recording book.

As I retrieved it and headed back to the inquisition, I snatched a glance inside. Argh! The last entry was about four months ago. Calm down; maybe they test the fire alarm every six months.

I was soon disabused off that notion.

He took the book and looked at the entries, then pushed it across the table as if it had burned his fingers. “What do you call this?” he barked.

“A fire alarm test has to be carried out once a week and properly recorded in the official fire alarm test book. This has not been filled in since the end of the bloody war by the looks of it. You are the senior officer on duty and you have responsibility for the safety of your staff. This is not good enough; you will hear more about this. Call yourself a Sergeant?”

Two thoughts immediately entered my mind: the first was, ‘I am the sergeant’, quickly followed by thought two: “but, you are the senior officer on duty”.

I decided to hold my water.

Then, without warning, he stood up, gathered his things, and headed out of the office. At the door, he looked back and said he would return next morning, sharp at 09.00 hundred hours, asking if I would be the sergeant on duty. I said I would be. He turned and walked out, leaving his last remark in the air for me to catch, “Well things had better improve!”

I never did make him tea. He had a bloody flask.

Thursday dawned, and exactly on the stroke of nine, he swept into the office, nodded to the receptionist, and asked how she was in a kindly voice. He did not waste time asking after my welfare and immediately got on with his probe. The high point came early in the afternoon with the ‘record of foot patrols log,’ which did impress him, as it was complete right up till the previous day. There was not a lot else to write home about. With that, he collected his flask and headed back to the security of Divisional Headquarters.

Oh, the ‘record of foot patrols log’, the one that so impressed him.

After he left the office the previous afternoon, I looked at the foot patrol log. I am a quick learner. It had not been filled in for the previous three months, so I filled it in (three months’ worth of lies, all in my own handwriting). Thus evidencing the complete waste of public money involved in such futile demonstrations of control and lack of trust, involving meaningless activity analysis.

Of course, an inspection process is important, but it should not be to look after the body corporate and humiliate the staff; it should be to ensure the staff group is informed and supported to create a sustainable service for the community served.

He could not care less about the real issues; he simply wanted to throw his weight around and ensure I knew who was the boss. In doing so, he lost credibility in my eyes.